**Immigrant Alberto Castañeda Mondragón Severely Beaten by ICE Agents in Minnesota: A Harrowing Story of Violence and Recovery**

MINNEAPOLIS – Alberto Castañeda Mondragón says his memory was so jumbled after a beating by immigration officers that he initially could not remember he had a daughter and still struggles to recall treasured moments like the night he taught her to dance. But the violence he endured last month in Minnesota while being detained is seared into his battered brain.

He remembers Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents pulling him from a friend’s car on January 8 outside a St. Paul shopping center, throwing him to the ground, handcuffing him, then punching him and striking his head with a steel baton.

He recalls being dragged into an SUV and taken to a detention facility, where he said he was beaten again. The emergency room and the intense pain from eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages remain etched in his memory.

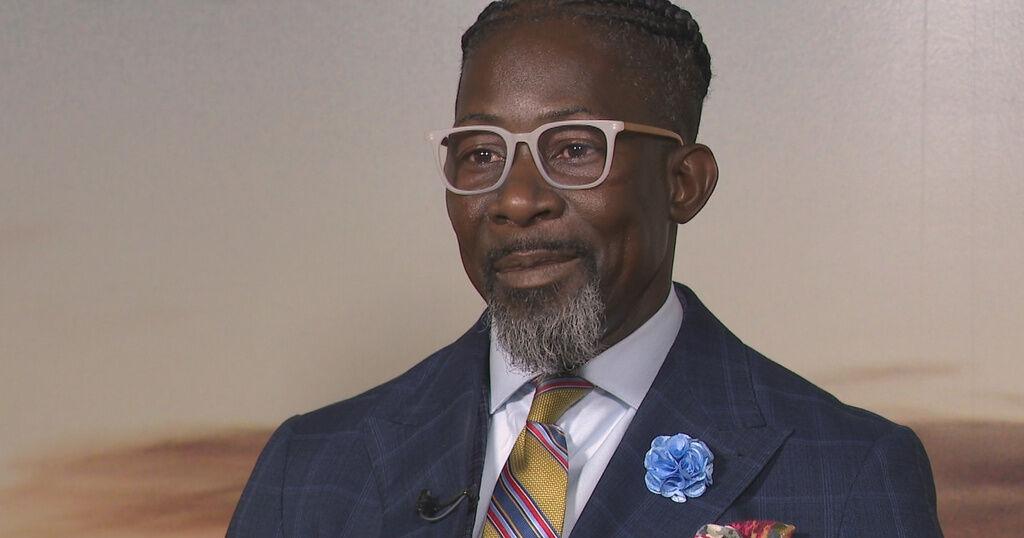

“They started beating me right away when they arrested me,” the Mexican immigrant recounted this week to The Associated Press, which recently reported on how his case contributed to mounting friction between federal immigration agents and a Minneapolis hospital.

Castañeda Mondragón, 31, is one of an unknown number of immigration detainees who, despite avoiding deportation during the Trump administration’s enforcement crackdown, have been left with lasting injuries following violent encounters with ICE officers. His case is among excessive-force claims the federal government has thus far declined to investigate.

—

### Disputed Account of Injuries

He was so badly hurt that he was disoriented for days at Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC), where ICE officers constantly watched over him. The officers told nurses Castañeda Mondragón “purposefully ran headfirst into a brick wall,” an account his caregivers immediately doubted.

A CT scan showed fractures to the front, back, and both sides of his skull—injuries a doctor told AP were inconsistent with a fall.

“There was never a wall,” Castañeda Mondragón said in Spanish, recalling ICE officers striking him with the same metal rod used to break the car windows. He later identified it as an ASP, a telescoping baton routinely carried by law enforcement.

Training materials and police use-of-force policies across the U.S. state that such a baton can be used to hit the arms, legs, and body, but striking the head, neck, or spine is considered potentially deadly force.

“The only time a person can be struck in the head with any baton is when the person presents the same threat that would permit the use of a firearm—a lethal threat to the officer or others,” said Joe Key, a former Baltimore police lieutenant and use-of-force expert.

—

### Continued Abuse at Detention Facility

Once taken to an ICE holding facility at Ft. Snelling in suburban Minneapolis, Castañeda Mondragón said officers resumed beating him.

Recognizing his serious injuries, he pleaded with them to stop, but they just “laughed at me and hit me again. They were very racist people,” he said. “No one insulted them, neither me nor the other person they detained me with. It was their character, their racism toward us for being immigrants.”

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which includes ICE, did not respond to repeated requests for comment on Castañeda Mondragón’s injuries. It is unclear whether his arrest was captured on body-camera footage or if there might be recordings from security cameras at the detention center.

In a recent attempt to boost transparency, DHS announced a broad rollout of body cameras for immigration officers in Minneapolis as the government also draws down ICE’s presence there.

ICE deportation officer William J. Robinson did not specify how Castañeda Mondragón’s skull was fractured in a January 20 declaration filed in federal court. The intake process determined he “had a head injury that required emergency medical treatment,” Robinson wrote.

The declaration also stated that Castañeda Mondragón entered the U.S. legally in March 2022 and that the agency only learned after his arrest that he had overstayed his visa. A federal judge later ruled his arrest unlawful and ordered his release from ICE custody.

—

### Video Shows Him Stumbling During Arrest

A video posted to social media captured the moments immediately after Castañeda Mondragón’s arrest, showing four masked men walking him handcuffed through a parking lot. The video shows him unsteady and stumbling, held up by ICE officers.

“Don’t resist,” shouts the woman recording. “’Cause they ain’t gonna do nothing but bang you up some more. Hope they don’t kill you,” she adds.

“And y’all gave the man a concussion,” a male bystander shouts.

The witness who posted the video declined to speak with AP or provide consent for its publication, but Castañeda Mondragón confirmed he is the handcuffed man seen in the recording.

At least one ICE officer later told medical center staff that Castañeda Mondragón “got his (expletive) rocked,” according to court documents filed by a lawyer seeking his release and nurses who spoke with AP.

—

### Hospital Staff Speak Out

AP interviewed a doctor and five nurses about Castañeda Mondragón’s treatment at HCMC and the presence of ICE officers inside the hospital. They spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing retaliation.

An outside physician consulted by AP affirmed the injuries were inconsistent with an accidental fall or running into a wall.

Minnesota state law requires health professionals to report to law enforcement any wounds possibly caused by a crime. An HCMC spokeswoman declined to confirm whether such a report was made.

Following the January 31 publication of AP’s initial story about Castañeda Mondragón’s arrest, hospital administrators opened an internal inquiry to determine which staff members had spoken to the media, according to internal communications reviewed by AP.

—

### Calls for Accountability from Public Officials

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz posted a link to AP’s prior story about Castañeda Mondragón on X (formerly Twitter), stating: “Law enforcement cannot be lawless. Thousands of aggressive, untrained agents of the federal government continue to injure and terrorize Minnesotans. This must end.”

Castañeda Mondragón’s arrest came a day after the first of two fatal shootings of U.S. citizens in Minneapolis by immigration officers, triggering widespread public protests.

Minnesota congressional leaders and elected officials including St. Paul Mayor Kaohly Her called this week for an investigation of Castañeda Mondragón’s injuries.

The Ramsey County Attorney’s Office urged him to file a police report to prompt an investigation. He said he plans to do so. A St. Paul police spokesperson confirmed the department will investigate “all alleged crimes reported to us.”

—

### Immigrant’s Background and Future Uncertain

While the Trump administration claimed ICE limits operations to immigrants with violent criminal records, Castañeda Mondragón has no criminal record.

“We are seeing a repeated pattern of Trump Administration officials attempting to lie and gaslight the American people about the cruelty of this ICE operation in Minnesota,” said Sen. Tina Smith, a Minnesota Democrat.

Rep. Kelly Morrison, a doctor and Democrat, toured the ICE facility at Ft. Snelling and reported observing severe overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and nearly nonexistent medical care.

“If any one of our police officers did this, you know what just happened in Minnesota with George Floyd—we hold them accountable,” said Democratic Rep. Betty McCollum, whose district includes St. Paul.

Originally from Veracruz, Mexico, Castañeda Mondragón came to Minnesota nearly four years ago on a temporary work visa and held jobs as a driver and roofer. He supports his elderly, disabled father and his 10-year-old daughter with his earnings.

On the day of his arrest, he was running errands with a friend when ICE agents surrounded them. They began breaking the vehicle’s windows and forcing doors open. He said the first officer who hit him “got ugly with me for being Mexican” and not having documents showing his immigration status.

—

### Hospitalization and Memory Loss

About four hours after his arrest, court records show, Castañeda Mondragón was taken to an emergency room in Edina, Minnesota, with swelling and bruising around his right eye and bleeding. He was then transferred to HCMC, where he told staff he had been “dragged and mistreated by federal agents,” before his condition worsened.

A week into hospitalization, caregivers described him as minimally responsive. As his condition slowly improved, hospital staff gave him his cellphone, and he spoke with his daughter in Mexico—whom he could not remember.

“I am your daughter,” she told him. “You left when I was 6 years old.”

His head injuries erased memories of past experiences unforgettable to his daughter, including birthday parties and the day he left for the U.S. She has been trying to revive his memory through daily calls.

“When I turned 5, you taught me how to dance for the first time,” she told him recently.

He said, “All these moments, really, for me, have been forgotten.”

He showed gradual improvement and, to the surprise of some treating him, was released from the hospital on January 27.

—

### Long Road to Recovery

Castañeda Mondragón faces a long recovery and an uncertain future. Questions remain about whether he can continue to support his family in Mexico.

“My family depends on me,” he said.

Though his bruises have faded, the effects of his traumatic brain injuries linger. He struggles with memory, balance, and coordination—disabling challenges for someone whose work involves climbing ladders.

“I can’t get on a roof now,” he said.

He also needs help with basic tasks like bathing.

Without health insurance, and unable to work, he relies on support from co-workers and Minneapolis-St. Paul community members who are raising money to help with food, housing, and medical care. He has launched a GoFundMe campaign.

Still, he hopes to stay in the U.S. and provide for his loved ones one day.

He draws a clear distinction between the people of Minnesota, where he has felt welcome, and the federal officers who beat him.

“It’s immense luck to have survived, to be able to be in this country again, to be able to heal, and to try to move forward,” he said. “For me, it’s the best luck in the world.”

—

### Fear and Trauma Persist

But when he closes his eyes at night, the fear that ICE agents will come for him haunts his dreams.

He is now terrified to leave his apartment.

“You’re left with the nightmare of going to work and being stopped,” Castañeda Mondragón said, “or that you’re buying your food somewhere, your lunch, and they show up and stop you again. They hit you.”

—

*This story underscores the ongoing debate over immigration enforcement practices in the United States and raises urgent questions about the use of force and accountability within ICE operations.*

https://www.npr.org/2026/02/07/g-s1-109219/immigrant-ice-arrest-beating